Via: variety.com By Chris Willman

As an aeronautical disaster movie, it ranks, but any serious characterizations of the famed Southern rock band are left up in the air.

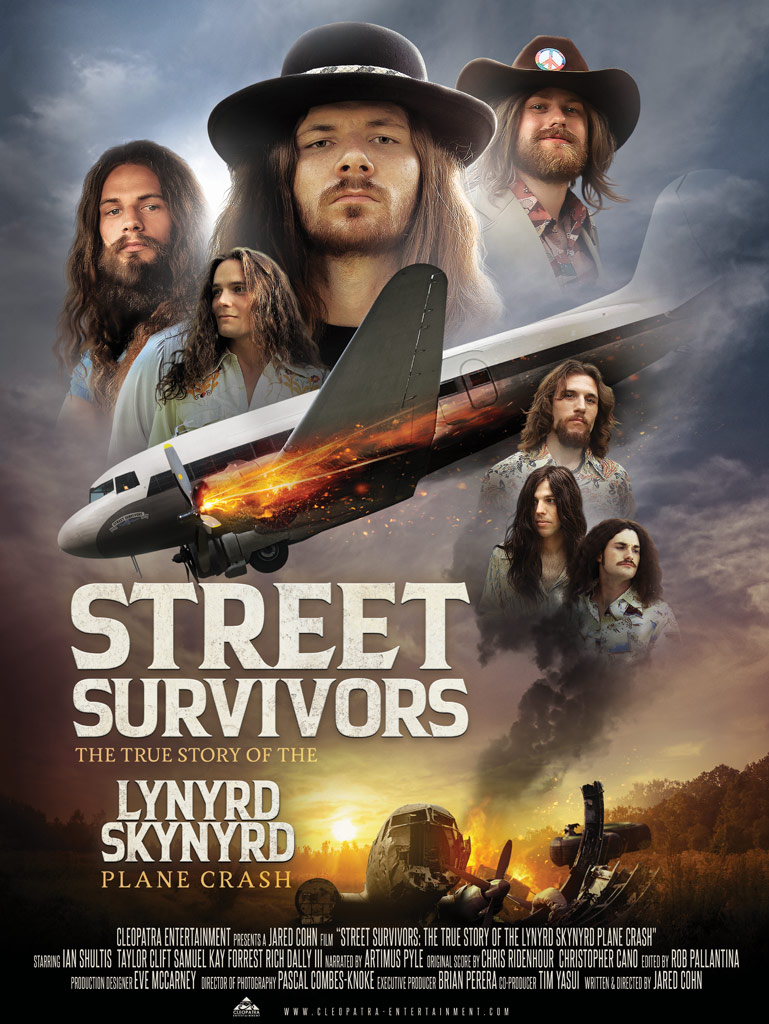

It may be a blessing of sorts for anyone interested in checking out “Street Survivors: The True Story of the Lynyrd Skynyrd Plane Crash” that its VOD release is coming in the middle of a pandemic, when not very many people are rushing to get back on planes again anyway. The film delivers on the promise — or threat — of its title in a big, vivid way, with enough drawn-out suspense once engines start backfiring and enough grisly carnage on the ground to give most viewers at least a second thought about flying again soon, at least on a prop-engine plane, and especially one with musicians on board. Despite its probably modest budget, “Street Survivors” is actually first-class as convincingly harrowing aeronautical disaster movies go, if you’re a follower of the genre that has Peter Weir’s 1993 “Fearless” to live up to.

Whether it’s a superior example of a rock biopic is another matter, as fans of the Southern rock band that was befallen by tragedy in 1977 are bound to be sharply divided about how it depicts the group in the days leading up to the calamity. Or how it doesn’t depict them: few of the band members come much into focus as the narrative unfolds, with the exception of drummer Artimus Pyle, who, now 71, shows up to introduce the film (and occasionally returns to narrate it) before turning things over to the actor who portrays his much younger self, Ian Shultis.

Pyle is apparently legally prohibited from participating in a movie that tells the full Lynyrd Skynyrd story, and other band members who survived or their estates filed a lawsuit trying to stop this one, although an appeals court eventually let him and the production company proceed. All that is to say that it may not have been a strictly artistic choice for writer-director Jared Cohn to keep some of the band members undefined, although doomed singer Ronnie Van Zant (Taylor Clift) does get plenty of time as a sort of mythological supporting player in Pyle’s story.

Once the real Pyle gets his on-screen prelude out of the way, the movie joins up with Shultis’ Pyle as a young man thrashing on the kit in his garage when he gets the call that Van Zant is interested in having him fill in for an erratic drummer who’s on the outs with the already famous band. Within minutes the film is already flashing forward to October of ’77, a few days before the fateful calamity. Somewhat to its credit, the movie doesn’t attempt to portray the group as star-crossed saints. There’s a casual verisimilitude that makes this part of the movie feel like it might actually have been shot in the ’70s, not just because of rampant, period-appropriate hairiness that makes it sometimes hard to tell all the hirsute faces apart, but in the rowdy banter that gets exchanged backstage, even as the topless romantic interests of the night come in and out of frame.

All good “Almost Famous”-style idylls must come to an end, of course, and this film starts toward its anxious mid-section with the procurement of a prop plane that Aerosmith has wisely turned down. (Members of that band are portrayed, too, for about half a minute, enjoying their own sex-and-drugs fringe benefits.) The very first flight on this new acquisition has some literally jolting moments, as one of the engines loudly backfires and shoots flames. There is much discussion about the wisdom of proceeding in such a jalopy, with pilots whose star-struckness doesn’t instill much professional confidence. But soon enough they’ve made a slow-mo ascent up the stairway — for the final time, in the case of six out of 26 on board — and eventually the plane is out of fuel and gliding toward a horrific landing in a Mississippi forest.

This is terrifically staged, especially considering that Cohn, visual effects supervisors Joseph J. Lawson and Eric Yalkut Chase, production designer Eve McCarney and DP Pascal Combes-Knokewere were likely not working with studio-level resources. The immediate aftermath is also riven with tension, in dizzying shots that have Pyle tending to survivors as well as surveying the perished. Once he runs off in search of help, we start to realize we’ll be spending the remainder of the third act with the heroically injured Pyle and none with those left behind with the wreckage.

Legally, the story may need to be all his, but in practicality it makes it feel as if the filmmakers didn’t much care about anyone else — save for the now-perished Van Zant, whom the script doesn’t quite know whether to treat as a TV-throwing jerk, a rock deity or both. Actually, even Pyle doesn’t come through as much of a character, beyond his eventual physical bravery. The last time we spend with the fictional Pyle, he’s getting screwed over by Skynyrd’s manager on contracts and medical bills, which is a slightly weird way to end a movie.

The film does offer an epilogue with the real guy playing a drum solo at a gig by his still active Artimus Pyle Band. There, as with the rest of the movie, no actual Skynyrd compositions are used, thanks to disputes that have festered since he departed from a reunion version of the group in the early ’90s. (The latest edition of the band, whose farewell tour was interrupted by the pandemic, has just one original member, Gary Rossington.) The soundtrack includes a good deal of ringer songs, largely co-written by Pyle and his children, along with one Skynyrd song the film could get rights to, a cover of J.J. Cale’s “Call Me the Breeze.” Needless to say, no one will exit “Street Survivors” humming the absent “Free Bird,” or being very high on flight at all.